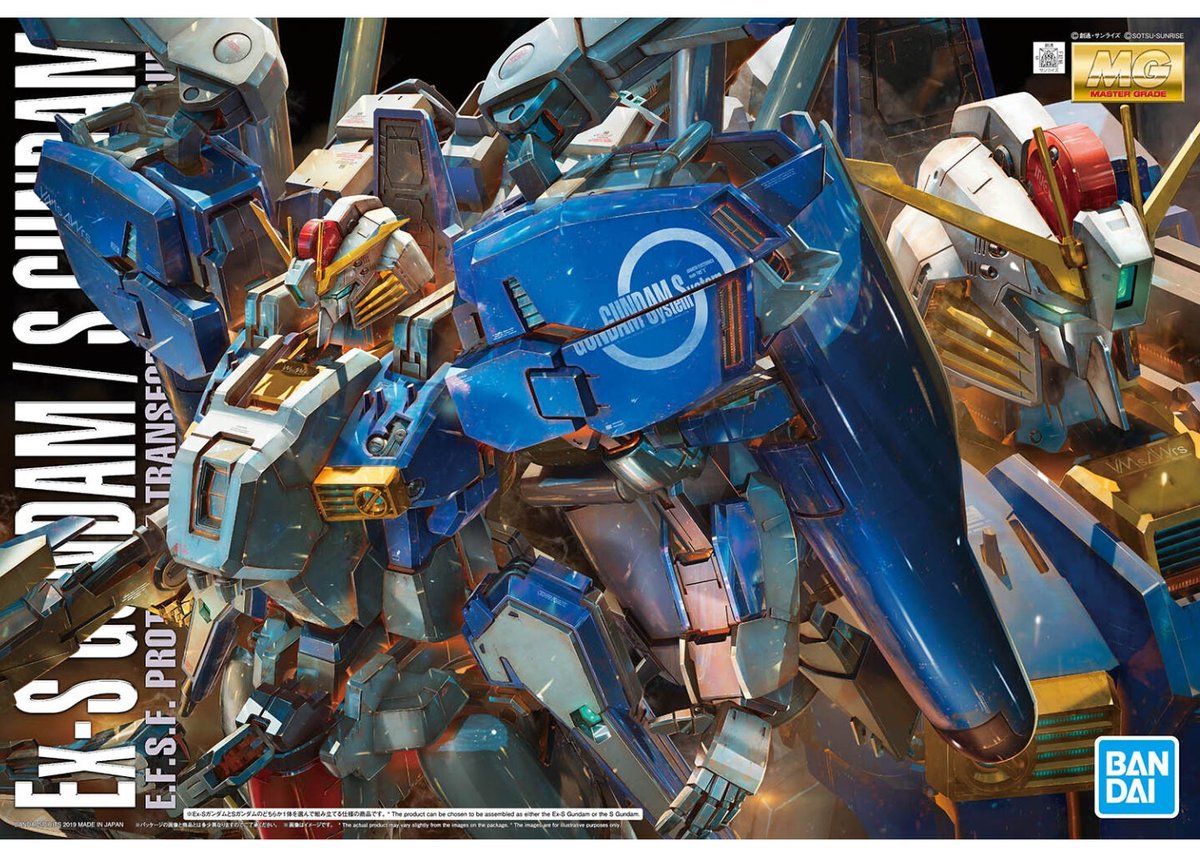

MG 1/100 Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム ver1.5 塗装済み 完成品

(税込) 送料込み

商品の説明

某オークションで完成品を購入し、短期間飾っていました。外箱もあります。

下記は作成した方の作品紹介を抜粋した物になります。ご参考にお読み下さい。

バージョンアップキットの方です。

【基本工作】

・パーティションゲート処理

・超音波洗浄

・塗装

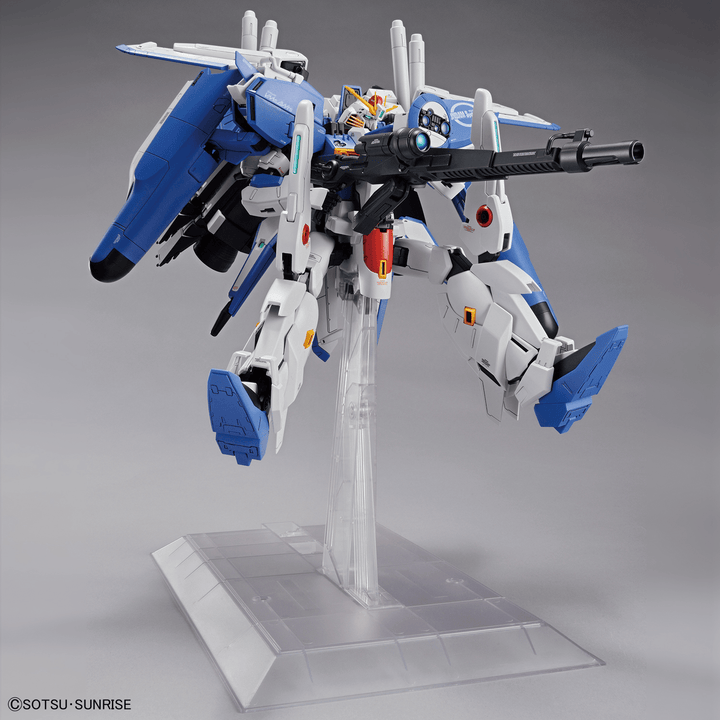

基本色ベごとのースサフで吹きつけを行い、PPカラーという30mlでもする塗料を基本に吹き付け塗装しています。

写真ではオフホワイト系に見えますが、ピュアホワイト系です。ブルーは、チネルブルー。

加えて、エッジをタミヤのウェザリングマスターを用い、立体感を出しました。

センサ-部もこだわって塗装しています。

・スミ入れ

原則コピック・ウォームグレー使用

・デカール

水転写デカールを使用

・仕上げ

クレオス・なめらかフラットに極微量のパールを混合して、吹きつけ

・改修

アポジモーターをアルミ素材に置換

おでこ部のセンサ-をSタイプのものに置換(完全固定はしてないので、ご注意ください))

【お譲りするもの】

・本体

・Gコア

・ビーム・スマートガン×1

・ビームサーベル×2

・スマート・ガン-本体固定パーツ

・インコムリード線ー×3

※X1-10、X1-1、2(線を曲げる丸いパーツと線を頭部に固定するパーツ)ナシ

・台座

・替えグリップ×5

・パッケージ

・設計図(設計に用いましたので、当然汚れあります)

ものすごいボリュームで、分離させるのがリスクのため、合体形態として制作しました。

分離・変形不可の合体ディスプレイ専用モデルとして展示ください。

※擦れによる塗装剥がれは当然あります。

※お約束ですが、所詮素人作品ですので、ノークレーム、ノーリターンでお願いします。

種類···ロボット

仕様···プラスチック組立キット

スケール···1/100商品の情報

| カテゴリー | ホビー・楽器・アート > 模型・プラモデル > その他 |

|---|---|

| ブランド | バンダイ |

| 商品の状態 | やや傷や汚れあり |

![MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver1.5 V27【ぷらもっち】](http://pla-mochi.com/11-gallery/0V/V27-Ex-S/1020B.jpg)

MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver1.5 V27【ぷらもっち】

![MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver1.5 V27【ぷらもっち】](http://pla-mochi.com/11-gallery/0V/V27-Ex-S/1050B.jpg)

MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver1.5 V27【ぷらもっち】

MG 1/100 EX-Sガンダム完成品 - 模型/プラモデル

MG 1/100 Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム ver1.5 塗装済み 完成品-

![MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver1.5 V27【ぷらもっち】](http://pla-mochi.com/11-gallery/0V/V27-Ex-S/1040B.jpg)

MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver1.5 V27【ぷらもっち】

Amazon | MG 機動戦士ガンダムセンチネル Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム 1

MG 1/100 Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム ver1.5 塗装済み 完成品-

Ex-Sガンダム プラモデル 完成品 MG ガンプラ マスターグレード

好評にて期間延長 MG 1/100 プラモデル Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム ver1.5

ガンプラ 完成品 MG ver1.5 ガンダム 塗装済み

EXーSガンダム mg 完成品 塗装済み-

MG 1/100 Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム | GUNDAM.INFO

MG EX-Sガンダム&MGガンダムmark V-

ガンプラ MG 1/100 Ex-Sガンダム / Sガンダム 未組立品-

Ex-Sガンダム プラモデル 完成品 MG ガンプラ マスターグレード

MG Sガンダム Ver.1.5 X14【ぷらもっち】

大量入荷 - 【MG完成品】Ex-sガンダム ver1.0スプリッター迷彩塗装

![MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Gクルーザーモード W01【ぷらもっち】](http://pla-mochi.com/11-gallery/0W/W01-ExS-WR/1010.jpg)

MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Gクルーザーモード W01【ぷらもっち】

ランキング1位受賞 1/100 プラモデル MG EX-s メルカリ EX-S Ex-S

EXーSガンダム mg 完成品 塗装済み-

MG 1/100 EX-Sガンダム完成品 abitur.gnesin-academy.ru

MG EX-Sガンダム/Sガンダム 組み立て済み-

Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム (MG) (ガンプラ) - ホビーサーチ ガンプラ他

MG 1/100 EX-Sガンダム完成品 abitur.gnesin-academy.ru

Yahoo!オークション -「mg 完成品 ex-sガンダム」の落札相場・落札価格

![MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver1.5 V27【ぷらもっち】](http://pla-mochi.com/11-gallery/0V/V27-Ex-S/1060B.jpg)

MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver1.5 V27【ぷらもっち】

Yahoo!オークション -「mg 完成品 ex-sガンダム」の落札相場・落札価格

1/100 MG Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム | HLJ.co.jp

変形・分離・合体!「MG Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム」のプレイバリューが

MG EX-Sガンダム&MGガンダムmark V-

ex-s ガンダム 塗装ランクS

MG Ex-Sガンダム / Sガンダム 完成品-

![MG 1/100 MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver 1.5 レジンキット AOK](https://blog-imgs-129.fc2.com/i/n/a/inaina18/O1CN01tEbvEA2KqVx2OotBy_!!136119608.jpg)

MG 1/100 MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Ver 1.5 レジンキット AOK

Yahoo!オークション -「mg 完成品 ex-sガンダム」の落札相場・落札価格

MasterGradeの頂点!! MG Ex-Sガンダム 改修・全塗装製作vol.1[gunpla

爆売り ガンプラ マスターグレード MG MSA-0011 Ext Ex-S GUNDAM S

![MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Gクルーザーモード W01【ぷらもっち】](http://pla-mochi.com/11-gallery/0W/W01-ExS-WR/1020.jpg)

MG MSA-0011[Ext] Ex-Sガンダム Gクルーザーモード W01【ぷらもっち】

MG,Ex-SガンダムSガンダム abitur.gnesin-academy.ru

2024年最新】MG EX-s 完成品の人気アイテム - メルカリ

MG 機動戦士ガンダムセンチネル Ex-Sガンダム/Sガンダム 1/100スケール

商品の情報

メルカリ安心への取り組み

お金は事務局に支払われ、評価後に振り込まれます

出品者

スピード発送

この出品者は平均24時間以内に発送しています